Finding the right frequency to adjust is, of course, the most important thing. With time you will get familiar with some of the most common frequencies, but what if you’re dealing with a new sound, or just don’t have the experience to know where to start? Here is an easy way to find the right frequencies to deal with.

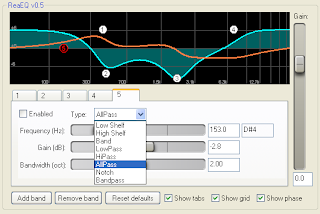

What you need is an EQ that allows you to control the target frequency. Boost one band all the way. If the band has a “Q” control make it quite high (Q stands for “quality factor” and it controls how wide the area affected by the boost or cut will be).

Then, play the sound and slowly sweep the frequency back and forth until you find the point where the tone you are looking to focus on is loudest. Make a note of the frequency and put the EQ back to zero. You now know the frequency where your target tone occurs and can cut or boost appropriately.

It’s a good rule that when cutting it’s best to use a narrow (high) Q, while it is better to have a wide (low) Q when boosting. This will help keep your EQ not excessively invasive.

The main reasons why it is better to cut than to boost is that excessive EQ boosting in a mix usually results in muddiness and loss of clarity, so as we already said, use eq with parsimony.

The low-mid range is where all the fullness and body lies for most of the instruments. For this reason it can be tempting to give those instruments plenty of low-mids. The problem is that all those low-mids fight for room in the mix and if you aren’t careful you’ll be left with an engulfed, unintelligible mess.

Think of your mix as a physical space: the more instruments you put in your mix, the harder it will be to fit everything in.

Therefore, more instruments in a mix, the more important it becomes to keep an eye on the areas where their tonal ranges tends to overlap. Each instrument needs its own place to sit in the mix, so any time there is a common range you need to choose which instrument takes the forefront in that frequency range.

For instruments that have the same basic range, such as bass and kick drum or two guitars, you can use the EQ to interlock them making them both distinct, unless you want a particular effect, as the "rhythm guitar wall of sound".

Talking about frequencies, and how to use them for single instruments, first off let's say that on the website RECORDINGEQ.COM there is a very interesting page with many standard frequencies, and the explanation of how they affect the mix, I think it's a great starting point as a reference, so check it out.

If we want to simplify, though, here are some eq references to begin with:

9KHz-15KHz:

Adding will give sparkle, shimmer, bring out details.

Cutting will smooth out harshness, and darken the mix.

Common processing: Very little compression, add/reduce gain for

timbral shaping.

6KHz-15kHz:

Air and presence.

Common processing: Slight gain boost.

4KHz-9KHz:

Brightness, presence, definition, sibilance, high frequency distortion.

Common processing: Compression to reduce sibilance/HF distortion. Add

(gain) brightness or liveliness to a mix.

5Khz-7KHz:

De-essing. Narrow band compression.

800Hz-4KHz:

Edge, clarity, harshness, defines timbre.

Common processing: gain reduction to reduce harshness.

200Hz-1.5KHz:

Punch, fatness, impact.

Common processing: Compression and gain boost.

150Hz-400Hz:

Boxiness.

Common processing: Reduce gain to remove 'mud'.

200Hz-below:

Bottom.

Common processing: Compression to tighten a boomy bass sound.

(source: http://www.dogsonacid.com/showthread.php?threadid=25008)

If we want to simplify, though, here are some eq references to begin with:

9KHz-15KHz:

Adding will give sparkle, shimmer, bring out details.

Cutting will smooth out harshness, and darken the mix.

Common processing: Very little compression, add/reduce gain for

timbral shaping.

6KHz-15kHz:

Air and presence.

Common processing: Slight gain boost.

4KHz-9KHz:

Brightness, presence, definition, sibilance, high frequency distortion.

Common processing: Compression to reduce sibilance/HF distortion. Add

(gain) brightness or liveliness to a mix.

5Khz-7KHz:

De-essing. Narrow band compression.

800Hz-4KHz:

Edge, clarity, harshness, defines timbre.

Common processing: gain reduction to reduce harshness.

200Hz-1.5KHz:

Punch, fatness, impact.

Common processing: Compression and gain boost.

150Hz-400Hz:

Boxiness.

Common processing: Reduce gain to remove 'mud'.

200Hz-below:

Bottom.

Common processing: Compression to tighten a boomy bass sound.

(source: http://www.dogsonacid.com/showthread.php?threadid=25008)

Focusing on ROCK/METAL GUITARS, my first suggestion is to try to get the right eq before recording, or directly on your guitar simulator, in order to modify it with vst equalizers in the most subtle and less invasive way possible.

First thing, let's remove everything you’re sure you won’t need, for example for someone, frequencies around 100hz are useless for a metal guitar, since it's a boomy area and taking it out will increase clarity. Next are the hiss, or fuzz frequencies which usually lie around 5050k, 8k, and 9650k. Dipping these frequencies by a few DB will take out the hiss, especially created by digital amp simulators, but can take some tone with them at times. Remember; it’s all experimentation!Someone prefers even to cut everything above 7khz (or more) to get a more mid-focused sound. To me it looks a little too much, better to low pass the sound starting by a higher frequency, like 12khz, and to high pass above 80hz.

Now we may add some EQ, lowering a little bit around 250hz and 650hz for a deeper scoop of middiness (if needed), and some 8k dip for clarity, to get rid of some of the boxiness.

About the frequencies to boost, it obviously depends on the type of sound, and more than often a good guitar sound doesn't need any boosting at all, but sometimes I found that adding a couple of dbs around 200hz and 3235hz may help to achieve a more aggressive sound.

Here are some of the best Free Vst Equalizers around:

Sonimus SonEq

http://sonimus.com/site/page/downloads/

Windows: VST

Mac: VST & AU

SPL Free Ranger

http://plugin-alliance.com/en/plugins/detail/spl_free_ranger.html

Windows: VST, RTAS, AAX

Mac: VST, AU, RTAS, AAX

Elysia Niveau Filter

http://plugin-alliance.com/en/plugins/detail/elysia_niveau_filter.html

Windows: VST, RTAS, AAX

Mac: VST, AU, RTAS, AAX

BX Cleansweep (Hi&Lo Pass Filter)

http://plugin-alliance.com/en/plugins/detail/bx_cleansweep_v2.html

Windows: VST, RTAS, AAX

Mac: VST, AU, RTAS, AAX

Variety of Sound Boot EQ mkII

http://varietyofsound.wordpress.com/vst-effects/

Windows: VST

CLICK HERE FOR THE PART 1/2 OF THIS TUTORIAL

CLICK HERE FOR A GUIDE ABOUT HOW TO RECOGNIZE THE FREQUENCIES!

Become fan of this blog on Facebook! Share it and contact us to collaborate!!

About the frequencies to boost, it obviously depends on the type of sound, and more than often a good guitar sound doesn't need any boosting at all, but sometimes I found that adding a couple of dbs around 200hz and 3235hz may help to achieve a more aggressive sound.

Here are some of the best Free Vst Equalizers around:

Sonimus SonEq

http://sonimus.com/site/page/downloads/

Windows: VST

Mac: VST & AU

SPL Free Ranger

http://plugin-alliance.com/en/plugins/detail/spl_free_ranger.html

Windows: VST, RTAS, AAX

Mac: VST, AU, RTAS, AAX

Elysia Niveau Filter

http://plugin-alliance.com/en/plugins/detail/elysia_niveau_filter.html

Windows: VST, RTAS, AAX

Mac: VST, AU, RTAS, AAX

BX Cleansweep (Hi&Lo Pass Filter)

http://plugin-alliance.com/en/plugins/detail/bx_cleansweep_v2.html

Windows: VST, RTAS, AAX

Mac: VST, AU, RTAS, AAX

Variety of Sound Boot EQ mkII

http://varietyofsound.wordpress.com/vst-effects/

Windows: VST

CLICK HERE FOR A GUIDE ABOUT HOW TO RECOGNIZE THE FREQUENCIES!

Become fan of this blog on Facebook! Share it and contact us to collaborate!!